Katarina Tadic

Serbian citizens are regularly asked if they are willing to accept recognition of Kosovo in exchange for EU membership. Unsurprisingly, the overwhelming majority said no, because Kosovo is an emotional question, whilst the EU has never managed to win over the hearts of people.

Serbian citizens are regularly asked if they are willing to accept recognition of Kosovo in exchange for EU membership. Unsurprisingly, the overwhelming majority said no, because Kosovo is an emotional question, whilst the EU has never managed to win over the hearts of people.

With the new government in Kosovo and the change in the US administration, the dialogue between Belgrade and Pristina is entering a new phase. Many contested issues are on the table: missing persons, association of Serb majority municipalities, protected areas around Orthodox churches and monasteries, etc.

Meanwhile, Kosovo PM keeps repeating that the comprehensive agreement can only bring recognition, while Serbia persists in repeating that recognition is not an option. The negotiations are stalled, and it is difficult to predict what are the concessions (if any) each side is willing to make. Despite the involvement and recent synchronization of both EU and US representatives, few are optimistic about the possibility of reaching an agreement soon.

I have recently been at a workshop where I was asked why it is so difficult for Serbia to recognise Kosovo. The impression is that many activists and intellectuals from the region believe that the authoritarian character of the regime of Aleksandar Vučić gives him absolute power and unlimited freedom to agree to any kind of proposal regarding Kosovo, facing no opposition at home.

However, whether one wants to admit it or not, the truth is that recognition of Kosovo today would be a political suicide for any politician in Serbia, including the highly popular president Vučić. Kosovo is first and foremost a symbolic and emotional issue in Serbia, and not a legal or political one, hence it is worth to treat it as such.

There are currently three features of the Serbian society that mutually reinforce each other standing in a strong opposition to any idea of independent Kosovo. I will only briefly elaborate each of them, fully aware that I am oversimplifying complex social, historical, and political phenomena.

Founding myths

First, every nation has its founding myths perceived as turning points in the collective destiny of the nation, and the key part of the Serb national identity is tied to the Kosovo myth. The Battle of Kosovo is the foundation of the modern Serb nationalism and it tells a story of the nation's struggle, demise, and reincarnation.

Kosovo is perceived as a cradle of Serb nation and culture, with numerous medieval orthodox churches and monasteries thus having “enormous historical and cultural significance for Serbs”.

The phrase “Kosovo is the heart of Serbia” was perhaps exploited by Slobodan Milošević, but it was effective only because it resonated well among Serbs and represented a mobilising tool based on the mainstream myth present in the collective memory.

A humiliated nation

Serbia (and Serbs) were a losing and condemned side in all wars in former Yugoslavia. Milosevic did not lose in 2000 due to sudden pacifist sentiments of Serbian people. He lost because Serbia had been defeated and humiliated for over a decade, culminating with the 1999 NATO bombing.

Similarly, in the following twenty years Serbian society never genuinely dealt with the criminal character of Milosević’s regime and crimes committed in our name. For instance, the Batajnica mass grave with 744 bodies of Kosovo Albanians had never found its way into the public discourse, thus placing crimes against Kosovo Albanians at the margins of the (civil) society.

As a result, the dominant feeling of being treated unfairly and ostracized by the international community that derives from the 1990s has only grown among Serbian population, the feeling additionally fueled by international demands to recognise Kosovo.

Source: pixabay.com

Source: pixabay.com

The Albanian Other

The third feature of Serbian society is related to the character of Serb nationalism and attitude towards Albanians. In the process of building any modern nation, “Others” are usually constructed as a must for forming the national identity and gaining national interests. And while for the creation, maintenance, and ultimately the breakup of Yugoslavia the relationship between Serb and Croat nationalism was crucial (they were each other’s “Other”), the nationalist mobilisation from the 1980s onwards particularly increased the resentment towards Kosovo Albanians.

With different language compared to other Yugoslav nations, Kosovo Albanians constitute a particularly significant and undesirable “Other”. In addition, during the nineties, when the conflict between Serbs and Albanians in Kosovo escalated, the Albanian Other was further dehumanised, and a ‘criminal Shiptar’ frame was constructed justifying Serbia’s atrocities against Kosovo Albanians.

Is there a way forward

In the last decade, since the start of the Brussels dialogue, Serbian citizens are regularly asked if they are willing to accept recognition of Kosovo in exchange for EU membership. Unsurprisingly, overwhelming majority said no, because Kosovo is an emotional question, whilst the EU has never managed to win over the hearts of people. Also, to recognise Kosovo and be the only former Yugoslav republic to lose one part of the territory is difficult to accept for an already humiliated society.

To be clear, I am not arguing that these characteristics of Serbian society and Serb nationalism are reasonable (can any nationalism be reasonable, after all) or that they should be used as an excuse for a status quo or for inflammatory rhetoric that we often hear from Serbian politicians and media. Reaching an agreement and reconciliating are in the best interest of both Kosovo and Serbia.

However, I do argue that the described nature of Serbian society must be considered in any deliberation of even hypothetical solutions to this conflict or dispute, whatever you prefer to call it. And civil society can play a role in tackling some aspects of it, in a long term. In a short term, there is little chance that the attitudes of Serbs will change, with a recent survey showing that even if the Orthodox Church accepts the recognition of Kosovo, it will not have an influence on the attitude of most of the respondents.

Contribution of the civil society

There are things that civil society should more actively start doing to alter the societal attitudes and bring changes in relation to views on Kosovo status. As previously stated, Kosovo remains a mythical place in the minds of Serbian people. I myself first travelled to Kosovo as part of the visiting programme of the Youth Initiative for Human Rights. Throughout the years I have got to spend more time in Kosovo, with every visit leading to a better understanding of the “other” side, but also realizing how oddly it sounds to most in Serbia to say you have been in Kosovo.

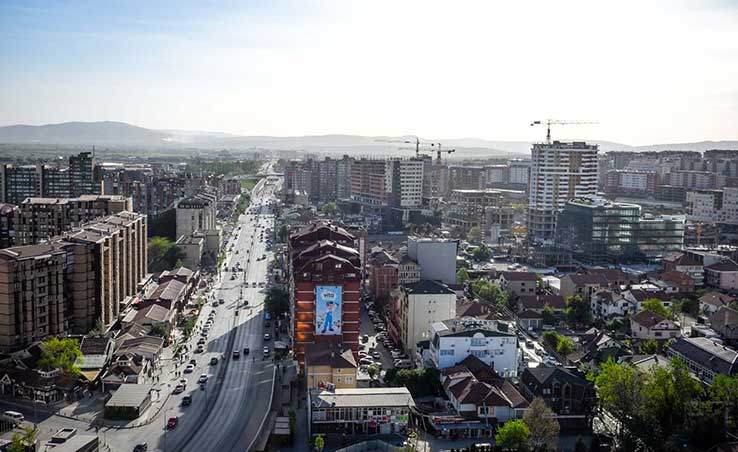

Visiting programmes and cultural exchanges would therefore be important for at least two reasons. They would be beneficial for the process of humanising Kosovo Albanians and going beyond the perception of seeing Kosovo purely as a piece of land and Albanians as undesirable Others. Being physically present in Pristina, Gazimestan or Mitrovica with fellow Albanians takes out the mythical element of those places providing a new context for understanding the current circumstances.

Cultural exchanges would be important for getting to know each other and have a frank conversation about the past. Being exposed to Albanian language and culture would reduce the ethnic distance and at least make Serbians familiar with it. Also, to deal with the past, you need to have knowledge about what happened in a form that is engaging to, unfortunately, uninformed public. “Miredita, dobar dan” is the only festival in Serbia that once a year for a few days promotes the culture of Kosovo Albanians in Belgrade. It is minimal and also centralised only to the capital.

Instead of conclusion

The general belief and perception is that Western countries are supporting Serbian strongman Vučić because he can deliver on Kosovo. Resolving the status of Kosovo would symbolically be a huge success for an otherwise limited foreign policy influence of the EU but also for the US administration. However, for all reasons stated above, and despite the international pressure, it is unrealistic to expect that Serbia will sign the recognition of Kosovo under these circumstances. And it is an illusion to argue that Vučić has total control over Serbian society that allows him to sign whatever deal he finds appropriate.

Normalisation of relations between Serbs and Kosovo Albanians has been and will continue to be a long process. Efforts to know each other better are crucial, and civil society has to contribute to building that key link in the chain of this process. Yes, it will be a lengthy and arduous process but it is nevertheless the key task for our generation and a crucial contribution to future neighbourly relations in the region.

Please refer to the Terms before commenting and republishing the content.

Note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute of Communication Studies or the donor.